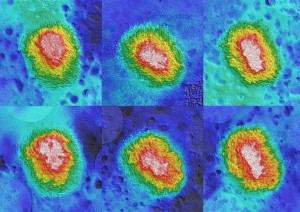

Inter-tidal reefs grow so quickly, they should be able to keep up with any future rate of sea-level rise. That’s good news because in the lower parts of estuaries oyster reefs need to maintain an intertidal elevation to thrive and the areal extent of oyster reefs is only a fraction of what it used to be before over harvesting. That rapid rate of growth is not sustainable because if it were it wouldn’t take long for a reef to be high and dry and oysters must be underwater at least half of the time. As you might expect, different parts of the reef grow at different rates. We have a new paper published in Nature Climate Change that presents the first reef-scale measures of growth. Our work shows that oyster-reef restoration has a high probability of success in inter-tidal areas. If inter-tidal reefs are restored close to marsh shorelines one could end up with a reef that will help protect the shoreline from erosion, filter water, provide fish habitat, and be able to keep up with sea-level rise. No rock sill can do those things.

My favorite part about the study is that it’s interdisciplinary (interface between ecology and geology) . There are lots of coauthors and I know the study would not have been completed without everyone’s contributions. If you keep visiting my site, in the future you will see more interdisciplinary oyster- reef studies, like their roll in the carbon and nitrogen cycles, comparing growth over multiple time scales, and quantifying the relationship between aerial exposure and growth rate.