Methods, methods, methods was the key focus this summer for my project. My project aims to understand how different salt marsh – upland morphologies affect salt marsh transgression (landward movement) with physical factors like increasing rates sea-level rise and frequency of large storms.

I used to really hate reading the methods section of papers because they didn’t always make complete sense to me and I didn’t find them particularly thought-provoking. However, this semester I started to learn through a seminar class that I’m taking that methods really determine the validity of your science. For example, we read a paper where the authors used an age date from an axe found in a UK marsh, which really made us question how valid that date really was (how old was the axe when it was lost and the tree before the axe was made?). So, this summer we set out to solidify the methods that we were going to use for my project.

Carson, Molly and Tony (left to right) resting half-way through the marsh march.

We went to Cedar Island and trekked through a quarter-mile of Juncus romarianus marsh. As Molly describes it, it’s type two fun where it’s not really that fun in the moment but when you get back you only remember it as being a fun day with friends and colleagues. To give you some insight into how this day went, a quarter-mile doesn’t sound very far, but when you’re walking through the thickest Juncus you’ve ever seen in your life a quarter-mile seems like a marathon. Juncus is a super robust marsh plant that is tall and almost woody. It tapers off at the top (about eye-level) to a point that can and will puncture your skin. The goal of the day was to determine the depth of the contact between marsh sediment and upland soil. Unfortunately for us, that contact was not quite clear in the sediment.

This is what we thought the contact would look like…a color change.

This is what the contact between freshwater peat and saltwater peat looks like.

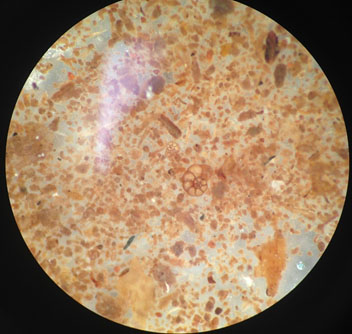

This is where we had to reevaluate our methods so that we could find a valid way to determine the contact between saltmarsh peat and freshwater peat. So, we headed back to the lab in search of a new way to verify the marsh-upland contact. I spent the next few weeks digging through the sediment, meticulously washing it, but very carefully to look for tiny creatures called foraminifera. Foraminifera are calcium-carbonate based creatures that only live in the water. Scientists have used foraminifera for years to try to build sea-level curves and determine past climate history. For us we were more interested in the presence versus absence of foraminifera because we wanted to use them to look down core and find the precise contact for the marsh-upland boundary. We can use this approach because foraminifera live in the marsh, but can only be transported into the upland through very high tide events, or storms. The difficult part of this was looking down a microscope for many hours a day, but also there was so much organic material blocking my view. Because foraminifera are delicate you can’t burn off the organic because the creatures fall apart. Instead, we used another approach where we tried to digest the organic material with hydrogen peroxide, but that didn’t work either because we ended up losing the forams along with only a portion of the organics. In the end we found simply isolating the finer particles with sieves and using a sample splitter on the remaining fraction was the best approach.

Microscope view of a sample. Notice the foram in the center.

Through all the failures this summer we had one major success. We determined that you can indeed use foraminifera to determine the contact between marsh and upland, and you can do it very precisely based on how many segments you cut your core into. We sectioned ours at 1-cm increments, so we were able to determine that contact at a centimeter precision. Even though I read many papers that used different methods for separating foraminifera from saltmarsh peat it’s important to try methods out on preliminary samples before collecting a complete dataset.